Magdalene

in The Last Supper?

"Which one is the painting?" Sophie

asked, scanning the walls.

"Hmmm..." Teabing made a show of seeming to have forgotten.

"The Holy

Grail. The Sangreal. The Chalice." He wheeled suddenly and

pointed to the far wall. On it hung an eight-foot-long print of

The Last Supper, the same exact image Sophie had just been looking

at. "There she is!"

Sophie was certain she had missed something. "That's the same

painting you just showed me."

He winked. "I know, but the enlargement is so much more exciting.

Don't you think?"

Sophie turned to Langdon for help. "I'm lost."

Langdon smiled. "As it turns out, the Holy Grail does indeed

make an appearance in The Last Supper. Leonardo included her prominently."

"Hold on," Sophie said. "You told me the Holy Grail

is a woman. The Last Supper is a painting of thirteen men."

"Is it?" Teabing arched his eyebrows.

"Take a closer look."

Uncertain, Sophie made her way closer to the painting, scanning

the thirteen figures - Jesus Christ in the middle, six disciples

on His left, and six on His right. "They're all men,"

she confirmed.

"Oh?" Teabing said. "How about

the one seated in the place of honor, at the right hand of the Lord?"

Sophie examined the figure to Jesus' immediate

right, focusing in. As she studied the person's face and body, a

wave of astonishment rose within her. The individual had flowing

red hair, delicate folded hands, and the hint of a bosom. It was,

without a doubt... female.

"That's a woman!" Sophie exclaimed.

Teabing was laughing. "Surprise, surprise. Believe me, it's

no mistake. Leonardo was skilled at painting the difference between

the sexes."

Sophie could not take her eyes from the woman beside Christ. The

Last Supper is supposed to be thirteen men. Who is this woman? Although

Sophie had seen this classic image many times, she had not once

noticed his glaring discrepancy.

"Everyone misses it," Teabing said.

"Our preconceived notions of this scene are so powerful that

our mind blocks out the incongruity and overrides our eyes."

"It's known as skitoma," Langdon added. "The brain

does it sometimes with powerful symbols."

"Another reason you might have missed the

woman," Teabing said, "is that many of the photographs

in art books were taken before 1954, when the details were still

hidden beneath layers of grime and several restorative repaintings

done by clumsy hands in the eighteenth century. Now, at last, the

fresco has been cleaned down to Da Vinci's original layer of paint."

He motioned to the photograph. "Et voila!"

Sophie moved closer to the image. The woman to

Jesus' right was young and pious-looking, with a demure face, beautiful

red hair, and hands folded quietly. This is the woman who singlehandedly

could crumble the Church?

"Who is she?" Sophie asked.

"That, my dear," Teabing replied, "is

Mary Magdalene."

(Chapter 58, pp. 242-243)

This long passage

is worth quoting in full largely because it is probably the part

of the book which has caught most readers' imaginations. Unlike

many of the other subjects the novel touches on (the Knights Templar,

the Holy Grail, the Gnostic gospels) Leonardo's The Last Supper

is something with which all Brown's readers would be very familiar.

And unlike those more unfamiliar elements, this is one claim which

most readers would be able to check. It is not difficult for the

average reader to find a copy of The Last Supper in an art book

or online and 'see' Mary Magdalene next to Jesus for themselves.

Many readers, when they become aware of Brown's many other errors

and distortions, often cling to this one 'fact' because they feel

they have seen Magdalene in the painting with their own eyes. Once

they have read this passage in the novel and then looked at the

painting, they find it very difficult that this figure to Jesus'

right could be anything other than a woman and anyone other than

Mary Magdalene.

Unfortunately

for them, they tend to be looking at the painting with an untrained

eye. And the commentary on the painting given to them by Brown via

Langdon and Teabing is even more full of errors, distortions and

misinformation as anything else in the novel and so is an untrustworthy

guide to what they are seeing.

Brown's analysis

of the painting is lifted directly from Lynn Picknett and Clive

Prince's conspiracy theory The Templar Revelation, which

is where he gets most of his misinformation about Leonardo, his

art and his beliefs. In fact, there is not an art historian on earth

who agrees with Picknett and Prince's amateur opinion that this

figure is Magdalene.

Back

to Chapters

The

Last Supper

Leonard began

this mural (it is not a 'fresco', as Brown calls it) for his patron

Duke Ludovico Sforza of Milan in 1495 and completed it in 1498.

It measures 880 x 460 cms and covers one wall of the refectory,

or dining hall, of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Paintings of the Last Supper were a traditional theme for the decoration

of monastic refectories and in many ways Leonardo's work keeps to

the traditions of such paintings, though he departs from them in

some small but significant ways. On the whole, however, he is faithful

to the story of the Last Supper told in the gospel of John (John

13-18).

Leonardo depicts

a specific incident in John's account: the moment after the supper

itself when Jesus announces one of his followers is going to betray

him (John 13:21-32). According to the gospel account Leonardo was

following, when Jesus announced this, his disciples were shocked

and dismayed. John ('the disciple Jesus loved') was reclining next

to Jesus, so Peter 'signed to him' (John 13:24) and said to him

'Ask (Jesus) who he means.' John asks this question of Jesus and

Jesus says it will be the man to whom he passes a piece of bread.

He then dips some bread in some sauce and gives it to Judas.

This is precisely

what Leonardo depicts. In his painting, Jesus sits serenely in the

middle of the twelve disciples, who are ranged on either side of

him in two groups of three. From the left they are Bartholomew,

James the Lesser and Andrew, then Judas, Peter and John. On the

other side of Jesus are Thomas, James Major and Philip and then

Matthew, Jude Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot. All are expressing

anger, alarm and dismay at Jesus' words, except Judas, who is leaning

back into shadow, turned partly towards Jesus and partly away from

the viewer.

Directly to

Jesus' right are John and Peter. As in the gospel account, Peter

is leaning forward, touching John's shoulder to get his attention,

pointing towards Jesus with his index finger and asking him to question

Jesus. John is leaning back toward Peter, his head down and listening

to what Peter is saying. It is also significant that Leonardo groups

Judas with these two. It is partly because Judas must be near Jesus

if Jesus could hand him the bread, but also because these three

represent three different standards of loyalty to Jesus: Judas betrays

him, Peter denies him and then repents and John stays with him until

his death.

Back

to Chapters

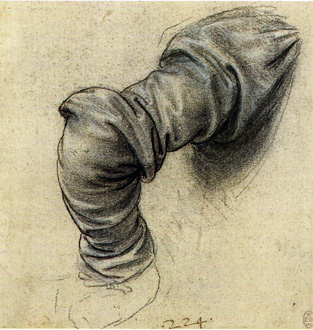

John

or Mary Magdalene?

So why does

this John figure look so much like a woman to the untrained modern

eye? This is largely because John was traditionally believed to

have been one of the only disciples who lived to an immensely old

age; dying, according to Christian traditions, on the island of

Patmos in the early Second Century AD. As a result, John was usually

depicted as being very young when he was a follower of Jesus in

the 30s AD. This

comparison of depictions of John from the time shows that

John was always shown as a teenager or beardless youth for

this reason. In fact, Jacobo Bassano's depiction of the Last Supper

goes so far as to show John as a young child.

For this reason,

the John in Leonardo's painting is one of only two men in the picture

who are beardless; the other being Philip, who was also traditionally

depicted as being younger than the others. In Leonardo's time it

was fashionable for youths and young men to be clean-shaven and

have shoulder-length hair, while older men often wore beards and

shorter hair, so John is shown without a beard and with 'flowing

red hair'. A comparison with other medieval and renaissance depictions

of John also shows that he was often depicted with red or reddish-brown

hair (see the link above).

But there are

two other reasons Leonardo's depiction of John looks feminine to

modern eyes. Firstly, the aesthetics of male beauty in youths in

Leonardo's time was decidedly feminine compared to modern tastes.

A youth who was considered attractive tended not to be ruggedly

handsome and burly, but rather delicately featured, fair and rather

girlish. This was particularly the case for Leonardo's depictions

of such young men.

Brown has Teabing

assure Sophie ' "Believe me, it's no mistake. Leonardo was

skilled at painting the difference between the sexes." ' In

fact, Leonardo is renowned for painting figures of ambiguous

sex. Angels were traditionally depicted as young men, but Leonardo's

angels could easily be mistaken for girls. And Leonardo did one

painting of another young John - John the Baptist - which, if the

viewer did not know who the painting was of, would easily be mistaken

for a young woman:

This sexual

ambiguity in Leonardo's depictions of young men was partly because

of the aesthetic of the time, but it could also have been influenced

by Leonardo's own sexuality. Despite Brown having Langdon claim

Leonardo was a 'flamboyant homosexual', the evidence about his sexuality

is actually unclear. He never married, he kept young men on as apprentices

despite their lack of artistic ability and, in one case, he kept

one on even though the young man had stolen from him. As a youth

in 1476 Leonardo was also accused, with three other young men, of

sodomy with a young male prostitute. After two hearings, the charges

were dropped because of lack of evidence and there is some speculation

the young plaintiff was a scam artist trying to blackmail the accused.

That said, there is certainly some evidence Leonardo was homosexual.

If this is the

case, it could go some way to explaining the way he liked to depict

young men in his art.

Back

to Chapters

John

= Salai?

Some art experts

have actually gone further with this idea. It is well known that

Leonardo had a favourite pupil in his studio: one Gian Giacomo Caprotti

da Oreno, better known by his nickname 'Salai', or 'the little devil'.

He was aptly

named. Leonardo took Salai into his home when the boy was aged ten

and made him one of his pupils. Salai was not a great artist, but

Leonardo cared for him and housed him until the time of the great

artist's death, after which he left a vineyard to Salai in his will.

This was despite the fact Salai ran away several times, stole from

Leonardo on several occasions and was noted for his theivery, bad

manners and gluttony. Leonardo himself wrote in exasperation that

Salai was 'theivish, lying, obstinate and greedy'.

While there

is no clear evidence that Leonardo was gay, it is widely thought

that he put up with Salai's behaviour because the pair were lovers.

Judging from a drawing of Salai by Leonardo, he was clearly a very

attractive, rather girlish-featured young man, with flowing hair

and large eyes. In fact, this drawing is so close to the figure

of John in The Last Supper in its pose and its features that it

is thought Salai was the most likely model for the John figure in

the painting. This becomes clear when the two figures are superimposed:

Drawing of Salai

by Leonardo

Detail of John,

from The Last Supper

Salai and John

superimposed 1

Salai and John

superimposed 2

The pose, the

features and the boy's nose and small, feminine chin are identical

in both pictures. In fact, the only differences are that John's

eyes are downcast and Salai is smiling, which makes sense considering

the circumstances of the gospel scene Leonardo is depicting in The

Last Supper.

So a good case

can be made that John looks feminine because he is based on the

feminine youth, Salai.

Back

to Chapters

The

Restorations of The Last Supper

Teabing assures

Sophie that one of the reasons art experts have not noticed 'Mary'

in The Last Supper before is that the painting has been clumsily

'restored', touched up and generally tampered with over the centuries.

He states that the recent expert and painstaking restoration work

completed in 1954 has revealed 'details …. hidden beneath layers

of grime and several restorative repaintings done by clumsy hands

in the eighteenth century.' He then declares 'Now, at last, the

fresco has been cleaned down to Da Vinci's original layer of paint

…. Et voila!"'

It is entirely

true that the painting was obscured and altered by repeated and

often clumsy restoration attempts over the centuries. Contrary to

Brown's repeated use of the word 'fresco' in relation to the painting,

it is actually painted in an experimental oil and tempera mixture

directly onto the stone of the wall; not onto wet plaster, as in

a true fresco. This allowed Leonardo to go back and make adjustments

to the painting over the four years he worked on it. Unfortunately,

it also meant the painting began to deteriorate soon after it was

completed. In 1517, Antonio de Beatis noted that The Last Supper

was falling apart and in 1726 Michelangelo Bellotti began the first

of several attempts at 'restoration'.

Bellotti cleaned

it with caustic solvents and then covered it with layers of oil

paint and varnish to try to restore and preserve it. In 1770 Giusseppe

Mazza removed much of his predecessor's work and then touched it

up with oil paints. Then, in 1853, Stefano Barezzi tried to remove

the painting from the wall altogether and, when that failed, tried

to glue the paint fragments to the base to prevent further decay.

These attempts all served to further damage the painting and it

was only in the Twentieth Century that more scientific approaches

to careful restoration were undertaken.

It was only

in 1903 that Luigi Cavengahi finally determined that the painting

was not done simply in oil, but in an oil and tempera mix. Between

1906 and 1908 he cleaned the painting carefully and retouched some

areas. It was cleaned again in 1924 by Oreste Silvestri.

The Last Supper

suffered again in 1943, when it was almost destroyed by bombing.

It was protected by sandbags and reinforcing braces, but the bombed-out

refectory remained open to the elements for some years before it

was repaired. After the War, between 1951and 1954, Mauro Pelliccioli

cleaned the painting of mildew and protected it with a shellac-based

coating, helping to preserve the damaged work. This is the restoration

Brown has Teabing refer to, but it was did not 'down to Da Vinci's

original layer of paint' as Teabing claims.

In fact, the

most recent, most scientific and most extensive restoration of The

Last Supper began in 1979 and was completed in 1999, under the guidance

of Pinin Brambilla Barcilon. Rather than simply cleaning and stabilising

the painting, Brambilla chose to actually remove the oil-based 'restorative'

overpainting from the Eighteenth Century, because it was eating

away at Leonardo's original pigments. Brambilla removed the over

painting and then repainted critical parts of the work in watercolour

in what she thought were the most likely colours and tones

used by Leonardo. Many hailed her 20 year project as a triumph of

preservation and restoration, but others savagely criticised it.

Professor James Beck of Columbia University's Art History department

in New York was a trenchant critic, arguing that the removal of

the over painting actually served to also remove more of Leonardo's

original pigments and that the watercolour additions were effectively

repainting the work all over again. Commenting to the BBC when the

restoration was unveiled in 1999 he said 'It's taking art lovers

for a ride. What you have is a modern repainting of a work that

was poorly conserved. It doesn't have an echo of the past.' (The

Last Supper Shown, BBC News, Thursday, 27 May, 1999)

Other critics

defended Brambilla's choices, but no-one would disagree that, in

many significant places, there is actually nothing of Leonardo's

original paint at all. Most importantly for readers of The Da

Vinci Code, almost none of the pigment on the faces of

the central figures is original.

So not only

is what Brown has Teabing claim about the most recent restoration

wrong, but - more importantly - his assertion that the restored

painting now reveals 'Da Vinci's original layer of paint' is pure

nonsense.

Back

to Chapters

Was

Mary Magdalene Defamed as a 'Prostitute'?

"That, my dear," Teabing replied, "is

Mary Magdalene."

Sophie turned. "The prostitute?"

Teabing drew a short breath, as if the word had injured him personally.

"Magdalene was no such thing. That unfortunate misconception

is the legacy of a smear campaign launched by the early Church.

(Chapter 58, p. 244)

The average

reader of The Da Vinci Code may know little about Mary Magdalene,

but the idea she was a prostitute before she met Jesus is deeply

ingrained in western culture. Painters from the Middle Ages to the

Modern Period traditionally depicted her with flowing, uncovered

hair (usually red), rich robes and youthful beauty - an image of

a wealthy whore. In periods where painters were usually commissioned

to paint the Virgin Mary or pious and chaste female saints and martyrs,

'Magdalene the Whore' gave them the license to insert the vaguest

hint of sex into their works. Modern depictions of her in the musical

Jesus Christ Superstar and The Last Temptation of Christ

reinforce this traditional image in the public mind, so Brown's

'revelation', via Teabing, that this was simply part of a Church

'smear campaign' has caught many readers' imaginations.

In fact, the

idea that she was a prostitute was never at any time part of the

doctrine of the Catholic Church or any other churches - it was simply

a popular folk-belief. Brown seems to have got the idea that it

was a deliberate 'smear campaign' from the fact that, on September

21, 591, Pope Gregory the Great gave an influential sermon where

he declared that Magdalene, Mary of Bethany, 'the woman taken in

adultery' described in John 8:3 and the woman who anointed Jesus'

feet in Luke 3 were all the same person. The word Gregory used to

describe this composite character was peccatrix, or 'sinner',

but he did not use the Latin word for 'prostitute' - meretrix.

The popular idea that Magdalene's 'sin' was sexual and that she

was, therefore, a prostitute certainly did arise from Gregory's

preaching indirectly, but neither Pope Gregory nor any other Church

leader ever maintained that she was a prostitute as a matter of

faith and doctrine.

In 1969 the

Second Vatican Council clarified the Church's teaching on Mary Magdalene,

correcting Pope Gregory's assertion that Mary Magdalene, Mary of

Bethany and the other two unnamed women were all the same person.

It also assured Catholics that the popular folk-belief that Magdalene

was a prostitute was without foundation. The media and some of Brown's

supporters have claimed this was some kind of belated reversal of

Pope Gregory's 'smear campaign', but it is clear that Gregory's

official Church doctrine never claimed Magdalene was a prostitute

in the first place and this was never taught by the Catholic Church

at any time.

As appealing

as it may be to some readers of the novel, the idea that Magdalene

was declared a prostitute by the Church as a smear is totally without

foundation. In an interview with Dan Burstein, Katherine Ludwig

Jansen - author of The Making of the Magdalene: Preaching and

Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages - was at pains to

reject the idea of any deliberate 'smear campaign':

In my view,

"cover-up" and 'conspiracy" are not useful ways to

understand the historical confusion about Mary Magdalene's identity

.... it would be a gross misinterpretation of history to view it

as a conspiracy or an act of maliciousness on (Pope Gregory's) part.

(Dan Burstein (ed.), Secrets of the Code: The Unauthorised Guide

to the Mysteries Behind The Da Vinci Code, p. 49)

Back

to Chapters

The

Marriage of Jesus and Magdalene

The Church needed to defame Mary Magdalene in

order to cover up her dangerous secret--her role as the Holy Grail."

"Her role?"

"As I mentioned, "Teabing clarified,

"the early Church needed to convince the world that the mortal

prophet Jesus was a divine being. Therefore, any gospels that described

earthly aspects of Jesus' life had to be omitted from the Bible.

Unfortunately for the early editors, one particularly troubling

earthly theme kept recurring in the gospels. Mary Magdalene."

He paused. "More specifically, her marriage to Jesus Christ."

"I beg your pardon?" Sophie's eyes moved to Langdon and

then back to Teabing.

"It's a matter of historical record," Teabing said, "and

Da Vinci was certainly aware of that fact.

(Chapter 58, p. 244)

This is one

of various points in the novel where Brown, through Teabing and

Langdon, assures the reader that the marriage of Jesus and Mary

Magdalene is 'a matter of historical record. Here Teabing asserts

that the gospels excluded from the canon of the Bible rejected 'earthly'

aspects of his life (such as this supposed 'marriage') and only

accepted a 'divine' being.

In fact, quite

the opposite is true. Despite Brown's various claims to the contrary,

the Gnostic gospels and others rejected from the canon tended to

depict Jesus as a purely spiritual, purely divine being who, at

best, only had the appearance of humanity. These texts had little

interest in or detail about his life, his actions, his friends and

family or anything human and concentrated almost exclusively on

his teachings or teachings they attributed to him. The canonical

gospels, on the other hand, depicted a much more rounded picture

of Jesus. This makes sense, considering they were written within

a few decades of the life of the man himself, before it became fully

encrusted with legend. In those Biblical gospels Jesus not only

has companions and family, enemies and debates and journeys and

miracles, but he also gets angry, expresses frustration, insults

his enemies, rejoices, eats and drinks and weeps at the death of

a close friend. Far from presenting some remote divine figure, the

Jesus of the canonical gospels is often, for modern Christians,

rather uncomfortably and authentically human. And, far from presenting

a more human Jesus, the later Gnostic texts actually depict him

as a one dimensional abstraction who is above and beyond any man.

Dan Brown's

characters actually get the story completely backwards.

In this passage

Brown has Teabing lead into the idea that the Gnostic gospels make

it clear that Jesus married Mary Magdalene and that, therefore,

this is 'a matter of historical record', but this is totally incorrect

on several levels.

Back

to Chapters

Mirror

Images in The Last Supper?

"It's a matter of historical record,"

Teabing said, "and Da Vinci was certainly aware of that fact.

The Last Supper practically shouts at the viewer that Jesus and

Magdalene were a pair."

Sophie glanced back to the fresco.

"Notice that Jesus and Magdalene are clothed as mirror images

of one another." Teabing pointed to the two individuals in

the center of the fresco.

Sophie was mesmerized. Sure enough, their clothes were inverse colors.

Jesus wore a red robe and blue cloak; Mary Magdalene wore a blue

robe and red cloak. Yin and yang.

(Chapter 58, p. 244)

This is one

of several places where Brown has Teabing insist that the marriage

of Magdalene and Jesus is 'a matter of historical record'. In fact,

there is no evidence at all that Jesus married Mary Magdalene or

anyone else.

Nor is there

any evidence that Leonardo was 'certainly aware of the fact' of

such a marriage. The entire thesis that he believed in this idea

is based on his supposed membership of the 'Priory of Sion', but

the evidence clearly shows that the 'Priory' was a Twentieth Century

hoax, so there is no way Leonardo could have been a member of a

secret society which did not exist in his time. All the evidence

we have about his religious beliefs indicates that they were entirely

unremarkable and we have zero evidence that he held any unorthodox

ideas or had any particular interest in Mary Magdalene.

As for the claim

that John and Jesus are a 'mirror image' of each other, there are

several figures in The Last Supper wearing similar shades of red

and blue, including one (Philip) who is also wearing both colours.

This is simply a matter of compositional balance. Leonardo grouped

the disciples into four trios, with Jesus as an isolated focal point

in the middle. The three disciples to the right of Jesus lean in

close to him, but John, Peter and Judas lean away. In order to tie

those three on the left of Jesus into the composition, Leonardo

made the colours of John's robes similar to those of Jesus

(not identical), but this choice has no significance other than

this.

Back

to Chapters

The

Mysterious Letter 'M'

"Venturing into the more bizarre,"

Teabing said, "note that Jesus and

His bride appear to be joined at the hip and are leaning away from

one another as if to create this clearly delineated negative space

between them."

Even before Teabing traced the contour for her, Sophie saw it-the

indisputable V shape at the focal point of the painting. It was

the same symbol Langdon had drawn earlier for the Grail, the chalice,

and the female womb.

(Chapter 58, p. 244)

The 'focal point'

of the painting is actually Jesus himself, not any 'negative space'

to his right. Leonardo used composition and colour to actually link

John's side of the painting to Jesus and any supposedly V-shaped

'negative space' was simply part of his composition.

"Finally," Teabing said, "if you

view Jesus and Magdalene as compositional elements rather than as

people, you will see another obvious shape leap out at you."

He paused. "A letter of the alphabet."

Sophie saw it at once. To say the letter leapt out at her was an

understatement. The letter was suddenly all Sophie could see. Glaring

in the center of the painting was the unquestionable outline of

an enormous, flawlessly formed letter M.

"A bit too perfect for coincidence, wouldn't

you say?" Teabing asked.

Sophie was amazed. "Why is it there?"

Teabing shrugged. "Conspiracy theorists

will tell you it stands for Matrimonio or Mary Magdalene. To be

honest, nobody is certain. The only certainty is that the hidden

M is no mistake. Countless Grail-related works contain the hidden

letter M - whether as watermarks, underpaintings, or compositional

allusions. The most blatant M, of course, is emblazoned on the altar

at Our Lady of Paris in London, which was designed by a former Grand

Master of the Priory of Sion, Jean Cocteau."

(Chapter 58, p. 244)

The perfection

and obviousness of this 'flawless' (actually, rather lop-sided)

letter 'M' seems to lie purely in Brown's imagination. This supposed

'M' is not a 'certainty at all, and - like finding shapes in clouds

- it is not hard to 'find' several letters in the composition of

The Last Supper if you try hard enough.

Jean Cocteau

was not a 'Grand Master' of the so-called 'Priory of Sion' because

the hoax 'Priory' was not invented until some years after he died

in 1963. The 'M' on the altar of Our Lady of Paris actually stands,

not surprisingly, for 'Mary' - the Virgin's name.

Back

to Chapters

Did Jesus Marry?

Sophie weighed the information. "I'll admit,

the hidden M's are intriguing, although I assume nobody is claiming

they are proof of Jesus' marriage to Magdalene."

"No, no," Teabing said, going to a

nearby table of books. "As I said earlier, the marriage of

Jesus and Mary Magdalene is part of the historical record."

He began pawing through his book collection.

"Moreover, Jesus as a married man makes

infinitely more sense than our standard biblical view of Jesus as

a bachelor."

"Why?" Sophie asked.

"Because Jesus was a Jew," Langdon said, taking over while

Teabing searched for his book, "and the social decorum during

that time virtually forbid a Jewish man to be unmarried. According

to Jewish custom, celibacy was condemned, and the obligation for

a Jewish father was to find a suitable wife for his son. If Jesus

were not married, at least one of the Bible's gospels would have

mentioned it and offered some explanation for His unnatural state

of bachelorhood."

(Chapter 58, p. 245)

This assertion

that Brown makes through Langdon has convinced many of his readers

that Jesus would have had to have been married. In fact, holy celibacy

was not universally 'condemned' in Jesus' time at all - we have

many examples of Jewish holy men from that time who were celibate.

One branch of Jewish tradition - the rabbinical branch of the Pharisees

- seems to have frowned on the practice and, when it came to dominate

Judaism after Jesus' time, made marriage a religious duty, but they

and their teaching on the matter did not dominate Judaism in Jesus'

time.

The Jewish historian,

Flavius Josephus, makes it clear that the elite of one of the four

major Jewish sects of the time, the Essenes, practiced holy celibacy:

Although

(the Essenes) are Jews by birth, they love one another even more

than the others. They avoid pleasures as a vice and hold that virtue

is to overcome one's passions and not be subject to them. Marriage

is disdained by them. But they adopt the children of others while

still young, leading them like kin through their studies and impressing

them with their customs.

(Jewish Wars, 2:120)

Josephus' own

spiritual mentor, Bannus, was also a celibate hermit:

I was informed

that one, whose name was Banus, lived in the desert, and used no

other clothing than grew upon trees, and had no other food than

what grew of its own accord, and bathed himself in cold water frequently,

both by night and by day, in order to preserve his chastity, I imitated

him in those things, and continued with him three years.

(The Life of Josephus, 2:11)

The Jewish historian

Philo also described another Jewish sect he called the Therapeutae,

who lived in celibate communities in the desert. Like Bannus, the

Therapeutae and the Essenes, John the Baptist lived alone in the

desert and it seems that he too was celibate. Finally, the Christian

apostle Paul - a rabbi trained by the famous Pharisee Gamaliel -

states clearly in one of his letters that he is celibate and encourages

unmarried Christians in Corinth to avoid marriage if they can:

Now to the

unmarried and the widows I say: It is good for them to stay unmarried,

as I am. But if they cannot control themselves, they should

marry, for it is better to marry than to burn with passion.

(1Corinthians, 7:9)

So holy celibacy

was not common in Jesus' time, but it was far from unknown

or even highly remarkable. Later in his letter to the Corinthians,

Paul mentions (1Corinthians 9:5) that 'all the other apostles and

the brothers of the Lord and Cephas (Peter)' were all married but,

significantly, he does not mention Jesus in this list. Finally,

Jesus himself had very little to say in his reported teaching about

marriage, but he is reported as praising holy celibacy:

"For

some are eunuchs because they were born that way; others were made

that way by men; and others have renounced marriage because of

the kingdom of heaven. The one who can accept this should accept

it."

(Matthew 19:12)

It is clear

that Jesus was not married but, like some other Jews of his time,

chose to be celibate for spiritual reasons.

Back

to Chapters

The

Gnostic Gospels

Teabing located a huge book and pulled it toward

him across the table. The leather-bound edition was poster-sized,

like a huge atlas. The cover read: The Gnostic Gospels. Teabing

heaved it open, and Langdon and Sophie joined him. Sophie could

see it contained photographs of what appeared to be magnified passages

of ancient documents - tattered papyrus with handwritten text. She

did not recognize the ancient language, but the facing pages bore

typed translations.

"These are photocopies of the Nag Hammadi and Dead Sea Scrolls,

which I mentioned earlier," Teabing said. "The earliest

Christian records. Troublingly, they do not match up with the gospels

in the Bible."

(Chapter 58, p. 245)

It is strange

that Teabing has a book which reproduces the Dead Sea Scrolls under

the title The Gnostic Gospels, since none of the Dead Sea

Scrolls are 'gospels', Gnostic or even Christian. Contrary to Teabing's

assertion that the Dead Sea Scrolls are 'the earliest Christian

records', they are purely Jewish works which not only have nothing

to do with Christianity but which were, for the most part, composed

about 150 years before Jesus was even born.

Similarly, Teabing

seems to be under the impression that the Nag Hammadi texts, which

definitely were Gnostic Christian works, were 'scrolls',

when they were actually codices - an early form of folded and sewn

book.

Flipping toward the middle of the book, Teabing

pointed to a passage. "The Gospel of Philip is always a good

place to start." Sophie read the passage:

And the companion of the Saviour is Mary Magdalene. Christ loved

her more than all the disciples and used to kiss her often on her

mouth. The rest of the disciples were offended by it and expressed

disapproval. They said to him, "Why do you love her more than

all of us?"

The words surprised Sophie, and yet they hardly

seemed conclusive. "It says nothing of marriage."

"Au contraire." Teabing smiled, pointing to the first

line. "As any Aramaic scholar will tell you, the word companion,

in those days, literally meant spouse."

Langdon concurred with a nod.

Sophie read the first line again. And the companion of the Saviour

is

Mary Magdalene.

(Chapter 58, p. 246)

What Teabing

and Langdon neglect to tell Sophie is that the Gospel of Philip

was written around 138 AD at the very earliest (possibly

much later still) and so was written a whole century after Jesus'

time. This, on its own, makes it an unreliable source of accurate

biographical information about Jesus' life.

The writer of

Philip actually seems to have had little interest in Jesus' life

- the 'gospel' is actually a collection of sayings attributed by

the Gnostic teacher, Valentinus (c. 100-153 AD), to Jesus. It contains

little biographical detail, probably because the Gnostics did not

believe Jesus was a human at all and (contrary to Teabing and Langdon's

claims) were not interested in the human details of his life.

There are also

several problems with the passage Sophie reads. It should actually

read like this:

And the companion

of the [...] Mary Magdalene. [...] loved her more than all the disciples,

and used to kiss her often on her […]. The rest of the disciples

[...]. They said to him "Why do you love her more than all

of us?"

(Philip, 59)

The manuscript

is badly damaged in places and has a number of holes caused by ants.

This means several of the key words in the passage are actually

missing and the text Sophie reads contains possible guesses as to

what the missing words were. 'Mouth' is a possibility, for example,

for where Jesus (another guess) kissed Mary Magdalene.

That aside,

there are several reasons this text cannot be used as 'evidence'

Jesus married Magdalene. Teabing claims 'any Aramaic scholar will

tell you, the word companion, in those days, literally meant spouse'.

In fact, the opinion of any Aramaic scholar on the matter would

be irrelevant, since Philip is written in Coptic, not Aramaic. And

the word in question - 'koinonos' - is a Greek loan-word

anyway. In Greek, 'koinonos' meant 'companion', 'travelling

partner', 'business partner' or 'associate'. It is not used

to mean 'spouse', 'wife' or 'sexual partner' in any of its many

examples of usage in Greek, and it is not as though Koine Greek

lacked words for those concepts. There is no reason, therefore,

to assume it has those meanings here.

And the objection

of 'rest of the disciples' where they ask why Jesus loves Magdalene

more also argues against the idea the two were married. If Magdalene

were Jesus' wife, the answer to that objection would be clear -

he loves her more because he is married to her. The objection does

not make much sense if Brown's claims about this passage are true.

Modern readers

associate a kiss, especially one on the mouth, as a sign of sexual

love. But ancient people used such kisses as a greeting and as a

sign of fellowship. More importantly, the Gnostics also used such

a kiss as a symbol of the passing and sharing of secret gnosis

- the hidden 'knowledge' that gave their sect its name. Brown neglects

to mention that Philip depicts Jesus discussing this symbolic kiss

earlier in the text:

[Grace comes]

forth by him from the mouth, the place where the Logos came forth;

(one) was to be nourished from the mouth to become perfect. The

perfect are conceived thru a kiss and they are born. Therefore we

also are motivated to kiss one another- to receive conception from

within our mutual grace.

(Philip, 35)

Other Gnostic

texts make it equally clear that this initiate's kiss was symbolic,

not sexual. In the Second Apocalypse of James, Jesus is depicting

exchanging such a symbolic kiss with his brother, James:

And Jesus

kissed my mouth. He took hold of me saying, 'My beloved! Behold,

I shall reveal to you those things that the heavens nor the angels

have known. Behold, I shall reveal to you everything, my beloved.

Behold, I shall reveal to you what is hidden. But now, stretch out

your hand. Now, take hold of me'

(Second Apocalypse of James)

Clearly there

is nothing sexual about this kiss or his addressing his brother

as 'My beloved'. Brown has Teabing ignore this context and therefore

misinterprets the kiss in Philip with an anachronistically modern

understanding of the meaning of such a kiss.

Back

to Chapters

The

Gospel of Mary

Sir Leigh Teabing was still talking. "I

shan't bore you with the countless references to Jesus and Magdalene's

union. That has been explored ad nauseum by modern historians. I

would, however, like to point out the following." He motioned

to another passage. "This is from the Gospel of Mary Magdalene."

Sophie had not known a gospel existed in Magdalene's

words. She read the text:

And Peter said, "Did the Saviour really

speak with a woman without our knowledge? Are we to turn about and

all listen to her? Did he prefer her to us?"

And Levi answered, "Peter, you have always been hot-tempered.

Now I see you contending against the woman like an adversary. If

the Saviour made her worthy, who are you indeed to reject her? Surely

the Saviour knows her very well. That is why he loved her more than

us."

(Chapter 58, p. 247)

Teabing does

not 'bore' Sophie with these 'countless references to Jesus and

Magdalene's union', because they simply do not exist. This also

means these non-existent 'countless references' cannot have been

'explored ad nauseum by modern historians'. This is yet another

example of vague assurances of expert agreement and general references

to unnamed sources are used by Brown to bolster the credibility

of the 'information' his characters impart.

The Gospel

of Mary is not a gospel 'in Magdalene's words' because it dates,

at the earliest, to the late Second Century AD; or over 120 years

after Magdalene would have died. It reflects the religious politics

of that time - with Peter and Levi representing the Gnostics' orthodox

opponents and 'Mary' representing the Gnostic's belief in direct

revelation from God rather than the passing down of traditions about

Jesus from his original followers. The gospel itself does not make

it clear that the 'Mary' it mentions is Magdalene rather than Mary

of Bethany or any of the other Marys mentioned in early Christian

texts, but it seems a reasonable hypothesis.

Back

to Chapters

Mary

vs Peter

"The woman they are speaking of," Teabing

explained, "is Mary Magdalene. Peter is jealous of her."

"Because Jesus preferred Mary?"

"Not only that. The stakes were far greater

than mere affection. At this point in the gospels, Jesus suspects

He will soon be captured and crucified. So He gives Mary Magdalene

instructions on how to carry on His Church after He is gone. As

a result, Peter expresses his discontent over playing second fiddle

to a woman. I daresay Peter was something of a sexist."

Sophie was trying to keep up. "This is Saint

Peter. The rock on which

Jesus built His Church."

"The same, except for one catch. According to these unaltered

gospels, it was not Peter to whom Christ gave directions with which

to establish the Christian Church. It was Mary Magdalene."

Sophie looked at him. "You're saying the Christian Church was

to be carried on by a woman?"

"That was the plan. Jesus was the original feminist. He intended

for the future of His Church to be in the hands of Mary Magdalene."

(Chapter 58, p. 248)

Here Brown has

Teabing again refer to this late Gnostic text as an 'unaltered gospel',

when it is actually very much a later development within Second

Century Christianity which says more about the beliefs of that time

than it does about real events in Jesus' time, over a century and

a half before.

Teabing's interpretation

of this text and the Gospel of Mary generally is also very

strange. Despite what he claims, there is nothing in Mary to indicate

that Jesus intended Mary Magdalene to lead the Church, nor is this

idea found in any other Gnostic text or anywhere else at all. This

wild hypothesis is pure fiction. As for the Gnostic image of Jesus

as something of a 'feminist', this idea is based on a highly selective

reading of the Gnostic texts. Many Gnostic works actually seem to

be highly sexist and openly hostile to women, since the Gnostics

saw sex and conception as imprisoning more spiritual souls in the

physical world they sought to escape. The Jesus of another Gnostic

text, the Gospel of Thomas certainly does not sound like

'the original feminist':

Simon Peter

said to him, "Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of

life."

Jesus said, "I myself shall lead her in order to make her male,

so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males.

For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom

of heaven."

(Thomas, 114)

Back

to Chapters

The

'Disembodied Hand' in The Last Supper

"And Peter had a problem with that,"

Langdon said, pointing to The Last Supper. "That's Peter there.

You can see that Da Vinci was well aware of how Peter felt about

Mary Magdalene."

Again, Sophie was speechless. In the painting, Peter was leaning

menacingly toward Mary Magdalene and slicing his blade-like hand

across her neck. The same threatening gesture as in Madonna of the

Rocks!

"And here too," Langdon said, pointing

now to the crowd of disciples near Peter. "A bit ominous, no?"

Sophie squinted and saw a hand emerging from the crowd of disciples.

"Is that hand wielding a dagger?"

"Yes. Stranger still, if you count the arms, you'll see that

this hand belongs to ... no one at all. It's disembodied. Anonymous."

(Chapter 58, p. 248)

The slicing

of Peter's 'blade-like hand' across John's neck is another 'detail'

Brown has lifted directly from Picknett and Prince's The Templar

Revelation. In fact, Peter's hand is neither 'blade-like' nor

threatening. He is touching John on the shoulder to ask him to query

Jesus as to who is going to betray him. John is leaning towards

Peter to listen to his question. The fingers of Peter's hand are

curled, not 'blade-like', and the only finger which is extended

is the index finger, which is pointing towards Jesus.

This is also

nothing like the supposedly 'threatening gesture as in Madonna of

the Rocks' - a reference to the protective, open-handed gesture

of the Virgin over the head of her son Jesus (Brown muddles Jesus

with John and claims this gesture is 'claw-like' and 'threatening').

Peter is merely pointing towards Jesus as he talks to John about

him.

The claim that

the 'dagger' is held by a mysterious 'disembodied' hand is even

more ridiculous. The 'dagger' is actually a bread knife and the

hand that holds it is not 'disembodied' or 'anonymous' - it belongs

to Peter.

We know this

because the preliminary sketch for the figure of Peter that Leonardo

made in preparation for the painting still survives and is kept

in the Royal collection at Windsor Castle. This sketch clearly shows

that it is Peter who is holding this knife; something which is made

even more clear when that sketch is superimposed on the (damaged)

right arm of Peter in The Last Supper.

Detail of

the 'Disemboadied Hand' with the knife in The Last Supper

Leonardo's

study of the hand of Peter for The Last Supper

Combined

image of the Windsor Castle study and the final painting of Peter's

hand

Peter's clutching

of the bread knife is a symbolic prefigurement of a later episode

in the story - where Peter uses a sword to defend Jesus as Judas

betrays him to his captors. Once again, Brown's use of unreliable

amateurish 'sources' and his failure to check their claims means

he manages to totally mislead unwary readers.

Back

to Chapters

Magdalene

the Royal Princess?

Sophie was starting to feel overwhelmed. "I'm

sorry, I still don't understand how all of this makes Mary Magdalene

the Holy Grail."

"Aha!" Teabing exclaimed again. "Therein lies the

rub!" He turned once more to the table and pulled out a large

chart, spreading it out for her. It was an elaborate genealogy.

"Few people realize that Mary Magdalene, in addition to being

Christ's right hand, was a powerful woman already."

Sophie could now see the title of the family tree.

THE TRIBE OF BENJAMIN

"Mary Magdalene is here," Teabing said,

pointing near the top of the genealogy.

Sophie was surprised. "She was of the House of Benjamin?"

"Indeed," Teabing said. "Mary Magdalene was of royal

descent."

"But I was under the impression Magdalene was poor."

Teabing shook his head. "Magdalene was recast as a whore in

order to erase evidence of her powerful family ties."

Sophie found herself again glancing at Langdon, who again nodded.

She turned back to Teabing. "But why would the early Church

care if Magdalene had royal blood?"

The Briton smiled. "My dear child, it was not Mary Magdalene's

royal blood that concerned the Church so much as it was her consorting

with Christ, who also had royal blood. As you know, the Book of

Matthew tells us that Jesus was of the House of David. A descendant

of King Solomon - King of the Jews. By marrying into the powerful

House of Benjamin, Jesus fused two royal bloodlines, creating a

potent political union with the potential of making a legitimate

claim to the throne and restoring the line of kings as it was under

Solomon."

(Chapter 58. p. 248-249)

Brown's claim,

via Teabing, that Mary Magdalene was 'of royal descent' would be

news to historians. Even taking the much later information in the

non-canonical gospels into account, the data we have on Magdalene

is miniscule and none of it indicates anything about her origins

other than the fact she was from Magdala in Galilee. There is absolutely

nothing in any of the source material about her family, let alone

her ancestry.

Brown seems

to have got his idea that Magdalene was 'of royal descent' and came

from the Jewish tribe of Benjamin purely from a book by 'Margaret

Starbird' called The Woman with the Alabaster Jar.

'Starbird' (her

full real name is unknown, but her first name seems to have been

'Maureen') was originally a Catholic, but she departed from Catholicism

and mainstream Christianity when she read Holy Blood Holy Grail.

Without realising that this amateur book was based on the whole

'Priory of Sion' hoax, she separated from her Catholic faith and

began pursuing research regarding Holy Blood Holy Grail's

claims about Jesus and Mary Magdalene. Drawing on much later medieval

legends which seemed to indicate that Magdalene fled to France after

Jesus' crucifixion, 'Starbird' developed a complex 'history' of

Jesus and Mary's marriage which she published, in 1993, as The

Woman with the Alabaster Jar.

Her book was

welcomed by some feminists, New Agers and elements on the fringe

of liberal Christianity; including, oddly, the otherwise scholarly

and sensible American Episcopalian Bishop John Shelby Spong. Historians,

on the other hand, regarded her speculations and hypotheses as amateurish

nonsense.

Convinced of

Holy Blood Holy Grail's claims Jesus married Magdalene, 'Starbird'

asked herself why he would have chosen this particular woman. Judging

from the tiny amount of information available about her, there seemed

nothing special about Magdalene. 'Starbird' decided that, since

Jesus was supposedly a descendant of the distantly ancient Jewish

royal house of David, Magdalene must also have been of royal birth.

There was nothing in the evidence to indicate this at all but, despite

this, 'Starbird' decided that Magdalene 'must have been' of the

house of Benjamin, which was the tribe of the earlier Jewish king

Saul.

Both the house

(and tribe) of David and that of Benjamin were distant historical

concepts in Jesus and Magdalene's time. All Jews traced their distant

ancestry to one of the original twelve tribes of Israel - the descendants

of the legendary twelve sons of Jacob, the son of Abraham in the

early history of their people. But the idea that someone of the

'house of Benjamin' or the 'house of David' in the First Century

AD was actually a direct lineal descendant of Benjamin or David

was as unlikely as someone in the Twenty-first Century with the

Scottish surname 'McDonald' being a linear descendant of an ancient

Scotsman called 'Donal'.

That aside,

the idea that Magdalene was a member of the tribe of Benjamin is

supported by no actual evidence at all - it is purely a series of

hypotheses and leaps of imagination piled up by 'Margaret Starbird'

because it fitted with her ideas about Jesus and Mary. In fact,

the tribe of Benjamin's descendents tended to be from the south

of Judea, whereas Magdala - the village of Mary's origin - was far

to the north: on the south coast of the Sea of Galilee. 'Starbird'

claimed Magdalene was not from Magdala at all but was actually the

same person as Mary of Bethany, but Brown ignores this (historically

unlikely) technical detail.

The idea from

'Starbird' that Magdalene was from 'the house of Benjamin', that

she had 'royal blood' and that her supposed union with Jesus was

therefore religiously and politically significant is based on no

evidence at all - it stems purely from the speculations of an amateur

enthusiast.

Back

to Chapters

Sangraal

= 'Holy Blood'?

Sophie sensed he was at last coming to his point.

Teabing looked excited now. "The legend of the Holy Grail is

a legend about royal blood. When Grail legend speaks of 'the chalice

that held the blood of Christ'... it speaks, in fact, of Mary Magdalene

- the female womb that carried Jesus' royal bloodline."

The words seemed to echo across the ballroom

and back before they fully registered in Sophie's mind. Mary Magdalene

carried the royal bloodline of Jesus Christ? "But how could

Christ have a bloodline unless...?" She paused and looked at

Langdon.

Langdon smiled softly. "Unless they had

a child."

Sophie stood transfixed. "Behold," Teabing proclaimed,

"the greatest cover-up in human history. Not only was Jesus

Christ married, but He was a father. My dear, Mary Magdalene was

the Holy Vessel. She was the chalice that bore the royal bloodline

of Jesus Christ. She was the womb that bore the lineage, and the

vine from which the sacred fruit sprang forth!"

Sophie felt the hairs stand up on her arms. "But how could

a secret that big be kept quiet all of these years?"

"Heavens!" Teabing said. "It has been anything but

quiet! The royal bloodline of Jesus Christ is the source of the

most enduring legend of all time - the Holy Grail. Magdalene's story

has been shouted from the rooftops for centuries in all kinds of

metaphors and languages. Her story is everywhere once you open your

eyes."

"And the Sangreal documents?" Sophie

said. "They allegedly contain proof that Jesus had a royal

bloodline?"

"They do."

"So the entire Holy Grail legend is all

about royal blood?"

"Quite literally," Teabing said. "The

word Sangreal derives from San Greal--or Holy Grail. But in its

most ancient form, the word Sangreal was divided in a different

spot." Teabing wrote on a piece of scrap paper and handed it

to her.

She read what he had written.

Sang Real

Instantly, Sophie recognized the translation.

Sang Real literally meant Royal Blood.

(Chapter 58, p. 249-250)

Actually, the

French for 'royal blood' would have been 'le sang royal', as Sophie

should have known, as a French speaker. Even in Old French, 'Sang

Real' does not mean 'royal blood'. Brown's claim, via Teabing, that

the word 'Sangreal' apparently should have been two words comes

directly from a contrived argument by the authors of Holy Blood

Holy Grail, who took one late manuscript which copied the word

as two words and constructed this idea of 'royal blood' from that

one error.

The actual word

used in most versions of the story was 'Sankgreall' and the last

part of that word derived from the Latin 'gradale' - meaning 'a

serving platter'. It was only later that the 'grail' became a cup

and Brown's assertions about 'holy blood' are a contrived modern

misinterpretation.

Back

to Chapters | Back to Home | Back

to Topics